[ad_1]

from the surely-the-presumption-of-guilt-people-will-be-fair-and-unbiased dept

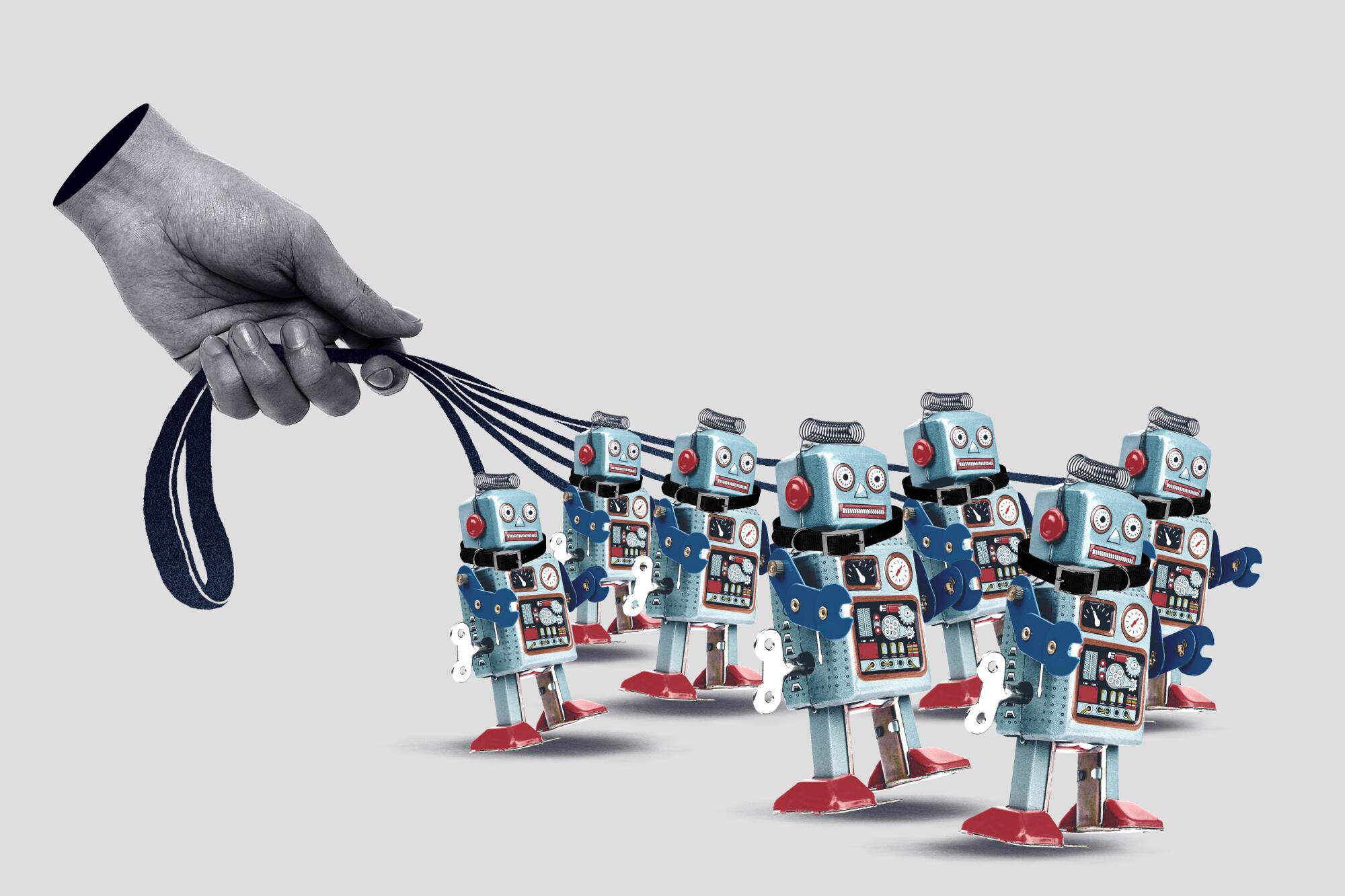

The justice system loves a stacked deck. Well, certainly the prosecutorial side loves it. Courts are, at best, ambivalent. Occasionally, this behavior gets called out.

When the DOJ made it clear it wasn’t really interested in a thorough examination of its many dubious forensic techniques, Judge Jed Rakoff resigned from just-formed “Forensic Science Committee” by pointing out the DOJ’s obvious disinterest in actual justice.

The notion that pre-trial discovery of information pertaining to forensic expert witnesses is beyond the scope of the Commission seems to me clearly contrary to both the letter and the spirit of the Commission’s Charter… A primary way in which forensic science interacts with the courtroom is through discovery, for if an adversary does not know in advance sufficient information about the forensic expert and the methodological and evidentiary bases for that expert’s opinions, the testimony of the expert is nothing more than trial by ambush.

Another federal judge (Don Willett of the Fifth Circuit Appeals Court) pointed out how qualified immunity stacks the deck against civil litigants, making it almost impossible to hold government employees accountable for clear rights violations.

Section 1983 meets Catch-22. Plaintiffs must produce precedent even as fewer courts are producing precedent. Important constitutional questions go unanswered precisely because those questions are yet unanswered. Courts then rely on that judicial silence to conclude there’s no equivalent case on the books. No precedent = no clearly established law = no liability. An Escherian Stairwell. Heads defendants win, tails plaintiffs lose.

In this case, we see another stacked deck. But not only does the court not care, it claims it’s ok for the deck to be stacked because it’s not four-of-a-kind, it’s just a flush. (h/t Matt Gillette)

An Arizona inmate a few weeks away from his execution is challenging the composition of the clemency board, which claims violates the law. Here’s what the law says:

Arizona law prohibits “No more than two members from the same professional discipline” from serving on the clemency board at the same time.

And here’s the state’s clemency board:

The current board is made up of: one former superior court commissioner and assistant attorney general; a former federal agent with over 30 years’ experience; a retired officer who spent 30 years with the Phoenix Police Department; and a 20-plus-year detective, also with the Phoenix PD. The fifth seat on the board is currently vacant.

One prosecutor and three law enforcement officers. It would seem to be a clear violation of the law prohibiting more than two people from “same professional discipline.” Somehow, Maricopa County Superior Court Judge Stephen Hopkins disagrees.

His decision [PDF] claims law enforcement isn’t even a profession, so having a bunch of people from the law enforcement side of the justice system doesn’t turn a clemency board into a “nope, get executed” board. First, the judge defines “profession,” using a lot of words that definitely sound like they could apply to law enforcement.

Historically, “professions” or “professionals” denoted doctors, lawyers, or the clergy as these were the only people that could read and write in Latin. Perks, R.W., Accounting and Society (Chapman & Hall 1993); BC Medical Journal, vol. 58, no. 5 (June 2016). That term has been broadened over the years. But it still typically denotes highly specialized work, advanced degrees, licensure, and adherence to a known and recognized set of standards. In other words, a profession is “a special type of occupation . . . (possessing) corporate solidarity . . . prolonged specialized training in a body of abstract knowledge, and a collectivity of service orientation . . . a vocational sub-culture which comprises implicit codes of behavior, generates an esprit de corps among members of the same profession, and ensures them certain occupational advantages . . . (also) bureaucratic structures and monopolistic privileges to perform certain types of work.” Turner, C. and Hodge, M.N., Occupations and Professions (1970).

Licensing, specialized training, implicit codes of behavior, esprit de corps, certain occupational advantages and monopolistic privileges… this all sounds like law enforcement.

But, no says this judge. It isn’t. How is it not that? Let’s let the judge explain.

Historically, law enforcement has not been thought of as a “profession.” It is not regulated as other professions are, and has little of the characteristics of what is typically considered a profession.

Go on…

Oh, I guess that’s it. There’s nothing else in there that explains how the judge arrived at this conclusion, other than by looking at the long list of profession features above and deciding within the space of two sentences does not apply to people commonly thought of as being part of “law enforcement.”

To prove he’s right, the judge offers an example that deliberately misconstrues the petitioner’s argument that all of the members “have a law enforcement background.”

Moreover, Petitioner’s definition of professional discipline is extremely broad. A person who worked for one week as a volunteer 9-1-1 operator is, under Petitioner’s definition, the equivalent of a forty year homicide detective.

That’s not what’s being argued. Every member of the board spent several years in the law enforcement profession, something that’s made clear by the judge’s footnote — one he apparently added in hopes of shoring up his own conclusions.

In simplistic terms, one member worked for Phoenix Police Department primarily as a homicide investigator and was then an employee of a security firm and later a city council member. One member was a Phoenix Police Department employee, as officer, detective, and supervisor in various assignments. One member was an ATF and DEA agent, and upon retirement was an educator at Glendale Community College. To the extent law enforcement may be considered a “profession” the Court finds from the information presented that each of these three members represent a different “discipline” within the large rubric of law enforcement based upon their employment histories.

These are all people who spent years, if not decades, in the field of law enforcement. I guarantee that, if asked, they would consider themselves to have been part of the law enforcement profession. They would have referred to themselves as law enforcement officers while working for law enforcement agencies. This decision is pure pedantry that ignores the common background of the board members to arrive at the conclusion they’re as unique as snowflakes.

All this does is ensure people facing the clemency board will find zero sympathy since everyone on the board was involved at one time or another in the business of locking people up. To decide this board’s make up isn’t problematic is to ignore the obvious in favor of the esoteric.

Filed Under: arizona, clemency board, police, profession

[ad_2]

Source link